A step closer to artificial cell division—by blowing bubbles

By blowing extremely small bubbles, researchers from the Kavli Institute of Nanoscience at Delft University of Technology (TU Delft) have found an efficient way of producing so-called liposomes – very small bubble-like structures often used to deliver medicine, but also key to generating artificial cells. The scientists publish their findings in the online edition of Nature Communications on Friday 22 January.

Cell division

One of the greatest challenges in the life sciences today is the assembly of an artificial cell from a set of individual components, an effort driven by the urge to improve our understanding of how biological cells work. One of the first steps on the road to generating such artificial cells is the ability to produce liposomes. These are very small, bubble-like structures with a lipid wall and filled with water. In this respect, they very much resemble empty "real" cells. Liposomes are already used for various purposes, including the delivery of drugs into the human body.

Lab on a chip

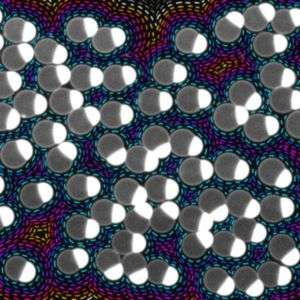

Researchers at TU Delft have now succeeded in producing liposomes in a very efficient way. They use a microfluidic 'lab-on-a-chip' technique to generate the structures assisted by minute liquid flows, in a process not unlike blowing soap bubbles (see video). "Ways of making liposomes already existed," says Siddharth Deshpande, a postdoctoral researcher in the team lead by Cees Dekker, "but these had significant drawbacks for our purposes. They were too slow and, above all, not pure enough."

1-octanol

The new 'bubbling-blowing' method uses a type of alcohol as a solvent. One of the problems with the earlier techniques was that they left behind an oily solvent residue in the liposomes. In search of a better alternative, Deshpande tried using 1-octanol instead. And the results exceeded all expectations, because the researchers observed that this substance moves quickly and spontaneously to one side of the newly-formed liposome, where it forms a droplet of 1-octanol which spontaneously separates from the host structure of its accord, within a few minutes.

"What remains," Deshpande explains, "are pure liposomes with the dimensions of a biological cell, 5-20 micrometres, and a lipid wall. We have since been able to show that this wall is very much like that of a 'real' cell – from a bacterium, for example."

Proteins

The new method has been dubbed octanol-assisted liposome assembly, or OLA. As Dekker explains: "OLA offers a flexible platform for producing the artificial cells of the future. We want to use the liposomes as the basic material for those cells. Our next goal is to make them divide by adding special proteins such as FtsZ and ZipA, which form rings around the 'equator' of the liposome. We are already conducting experiments with this technique. If they succeed, we could make 'soap bubbles' capable of producing autonomous daughter bubbles. This should give us spectacular insight into the mechanisms bacterial cells use to divide."

More information: Nature Communications, Siddharth Deshpande, Yaron Caspi, Anna EC Meijering, and Cees Dekker "Octanol-assisted liposome assembly on chip", DOI: 10.1038/NCOMMS10447

Journal information: Nature Communications

Provided by Delft University of Technology