'Pale orange dot': Early Earth's haze may give clue to habitability elsewhere in space

An atmospheric haze around a faraway planet—like the one which probably shrouded and cooled the young Earth—could show that the world is potentially habitable, or even be a sign of life itself.

Astronomers often use the Earth as a proxy for hypothetical exoplanets in computer modeling to simulate what such worlds might be like and under what circumstances they might be hospitable to life.

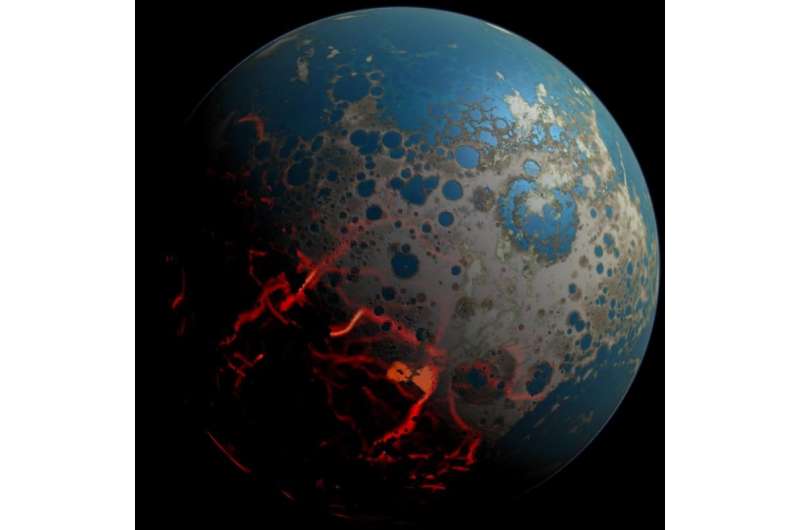

In new research from the University of Washington-based Virtual Planetary Laboratory, UW doctoral student Giada Arney and co-authors chose to study Earth in its Achaean era, about 2.5 billion years back, because it is, as Arney said, "the most alien planet we have geochemical data for."

The work builds on geological data from other researchers that suggests the early Earth was intermittently shrouded by an organic pale orange haze that came from light breaking down methane molecules in the atmosphere into more complex hydrocarbons, organic compounds of hydrogen and carbon.

"Hazy worlds seem common both in our solar system and in the population of exoplanets we've characterized so far," Arney said. "Thinking about Earth with a global haze allows us to put our home planet into the context of these other worlds, and in this case, the haze may even be a sign of life itself."

Arney and co-authors will present their findings Nov. 12 at the American Astronomical Society's Division for Planetary Sciences conference in National Harbor, Maryland.

The researchers used photochemical, climate and radiation simulations to examine the early Earth shrouded by a "fractal" hydrocarbon haze, meaning that the imagined haze particles are not spherical, as used in many such simulations, but agglomerates of spherical particles, bunched together not unlike grapes, but smaller than a raindrop. A fractal haze, they found, would have significantly lowered the planetary surface temperature.

However, they also found the cooling would be partly countered by concentrations of greenhouse gases that tend to warm a planet. They saw that this combination would result in a moderate, possibly habitable average global temperature.

Such a haze, the researchers found, also would have absorbed ultraviolet light so well as to effectively shield the Achaean Earth from deadly radiation before the rise of oxygen and the ozone layer, which now provides that protection. The haze was a benefit to just-evolving surface biospheres on Earth, as it could be to similar exoplanets.

The researchers also found that, based on the early Earth data, it's unlikely such a haze would be formed by abiotic, or nonliving means. So for exoplanets with Earthlike amounts of carbon dioxide in their atmospheres, Arney said, "organic haze might be a novel type of biosignature. However, we know these hazes can also form without life on worlds like Saturn's moon Titan, so we are working to come up with more ways to distinguish biological hazes from abiotic ones."

Co-author Shawn Domagal-Goldman of the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, said, "Giada's work shows that the haze could have intertwined with life in more ways than we previously suspected."

Arney added that astronomers often think of Earthlike exoplanets as "pale blue dots"—after a famous photo of Earth taken by the Voyager spacecraft—"but with this haze, Earth would have been a 'pale orange dot.'"

Provided by University of Washington