'Man-made' climate change a major woman's problem

Men and women may not always be on the same footing but you would think both sexes would be equal in the face of gigantic floods, typhoons or droughts. Think again.

Countless studies show that natural disasters on average kill more women than men—90 percent female fatalities in some cases, prevent girls from going to school, increase the threat of sexual assault. And the list goes on.

This issue has leapt to the fore in global negotiations on climate change, which scientists warn will be responsible for increasingly violent and frequent natural catastrophes around the world.

"It boils down to the fact that women and men have different types of vulnerabilities already in the world," said Tara Shine, special advisor to the Mary Robinson Foundation-Climate Justice think tank, headed by the former Irish president-turned UN special envoy for climate change.

"And then climate change comes along and accentuates all of those," she added on the sidelines of the ongoing UN Human Rights Council in Geneva, where the issue of climate change and rights was debated.

Cannot swim, climb trees

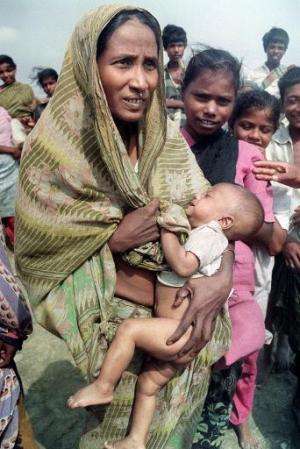

According to the World Bank, 90 percent of some 140,000 victims of the 1991 cyclone that battered Bangladesh were women, as were nearly two thirds of those killed by Myanmar's 2008 Cyclone Nargis.

"There are many reasons but one of them is that they cannot swim, they cannot climb trees, it's cultural," said Elena Manaenkova, assistant secretary-general of the World Meteorological Organization (WMO).

"In many countries—and it's also cultural—they are not supposed to run, they are supposed to wait until their husband will call them to action."

One of the WMO's objectives is to reach out to people in disaster-prone areas with forecasts that could save their lives or livelihoods, for which mobile phones are an important tool.

But according to Manaenkova, 300 million fewer women have mobile phones than men, which means warnings often do not reach them.

Beyond this, women and girls are also impacted by climate change in their everyday lives—education being a prime example.

In many parts of the developing world, for instance, they are the ones who fetch water for their families, and as global warming impacts the availability of fresh water sources, they have to trek farther afield to find them—meaning less time for school.

According to the United Nations Development Programme, a survey conducted in Tanzania found girls' attendance to be 12 percent higher for those in homes located near a water source than in homes one hour or more away.

Attendance rates for boys appeared to be far less affected.

Plan International conducted extensive research on the subject in 2010 in drought-ridden Ethiopia and flood-prone Bangladesh, and found the long walks were also dangerous.

"I know two girls who were raped going to fetch water. When you go far and there are not many people around, it happens," Endager, a 16-year-old girl from Lasta district in Ethiopia, was quoted as saying in the NGO's report.

Poverty-inducing natural disasters can also increase the propensity for child marriage.

"After cyclones, families think their condition is worse and send their daughters to get married," a young girl from Barguna in Bangladesh was quoted as saying.

"Almost 50 percent of girls drop out of education because of early marriage. In very remote villages, it is probably more 70 to 75 percent."

Often so 'obvious'

So what can be done? Simple, experts say—empower women, get them involved at all levels, and remember that they exist.

According to Shine, the issue is expected to feature prominently in a crucial new agreement aimed at averting catastrophic global warming to be signed in Paris later this year.

Some countries—such as Mozambique—are already factoring gender into their response to climate change, she says.

"When it (Mozambique) is increasing the resilience of smallholder farmers' livelihoods to the impact of climate change, it doesn't forget the majority of its smallholder farmers are women," she said.

"It therefore has to tailor the supports, advice and technologies that it makes available to them to be appropriate to their needs and to ask them what they want."

Other concrete measures include making sure typhoon shelters have separate female and male toilets, so women will feel safe and go there during a storm.

"It's often such obvious stuff but if the people responsible for it aren't a little bit aware that there are gender differences..., with all the good intention in the world, they can end up doing something that has a negative effect," said Shine.

© 2015 AFP