As lakes become deserts, drought is Iran's new problem

Nazar Sarani's village in southeast Iran was once an island. It is now a desert, a casualty of the country's worsening water crisis.

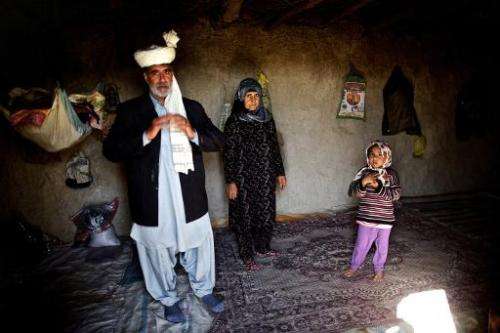

"We live in the dust," said the 54-year-old cattle herder of his home in the once exceptional biosphere of Lake Hamoun, a wetland of varied flora and fauna, which is now nothing but sand-baked earth.

Climate change, with less rainfall each year, is blamed, but so too is human error and government mismanagement.

Iran's reservoirs are only 40 percent full according to official figures, and nine cities including the capital Tehran are threatened with water restrictions after dry winters.

The situation is more critical in Sistan-Baluchistan, the most dangerous area in Iran, where a Sunni minority is centred in towns and villages that border Pakistan and Afghanistan.

Only 15 years ago, Hamoun was the seventh largest wetland in the world, straddling 4,000 square kilometres (1,600 square miles) between Iran and Afghanistan, with water rolling in from the latter's Helmand river.

But with dams since built in Afghanistan as well as other blocked pathways holding back the source of Hamoun's diversity, the local economy has collapsed.

Some 3,000 families whose lifeline was fishing have left and young people head to other provinces for work.

People are wasting water

A study in 2013 by the World Resources Institute ranked Iran as the world's 24th most water-stressed nation, with public consumption around twice the world average.

Government subsidies on water do nothing to encourage efficiency, and public education messages on television and radio are ignored.

Agricultural use—for water-heavy crops such as rice and corn—is thought to eat up nearly 90 percent of national supply, with experts saying irrigation is poorly managed, resulting in high wastage.

For those whose taps are running dry, the result is hardship and human turmoil: drug use is rising and sandstorms are causing respiratory illnesses.

Sarani's village, Sikhsar, where wooden boats sit on hard mud that was once the waterfront, is a place that mother earth has transformed.

The area once had several villages, 3,000 cows, lakes and birds.

Sarani's own herd used to number 100. Now down to just 10 cows, his depleted milk sales are not enough to feed the family or educate four children.

Most local youths have headed to the cities of Yazd, Semnan and Tehran to work as construction labourers.

The water problem is everywhere. Lake Urmia, a near 145-kilometre-long (90-mile), 48-kilometre wide salt lake near Iran's northwest border with Turkey, is almost empty.

And in the city of Isfahan, an ancient jewel long dubbed "half the world" for its beautiful palaces, boulevards, bridges and mosques, the Zayanderud river that runs through it is often bone dry.

Region warmer and drier

Much like Sarani, Mohammad Bazi, a fellow shepherd in Hamoun, bemoans what he says is government inaction in Tehran, arguing that Afghanistan must be persuaded to reopen the valves.

With the land so parched, he often has to walk his cattle hundreds of kilometres to find suitable grazing. The lack of water has also caused milk quality to decline and, struggling to survive, he has slaughtered some of his cows.

Massoumeh Ebtekar, Iran's vice president responsible for the environment, has said efforts are being made to protect Iran's water rights that will see it flow back across the border.

"We need local, regional, and international cooperation," she added.

The government is also working with the United Nations, but the challenges seem immense.

"The whole region is becoming warmer and drier," said Gary Lewis, head of the UN Development Programme in Iran, calling for the Iranian and Afghan governments at the highest level to tackle it.

"The situation is unsustainable," he added, noting climate change but naming water mismanagement as the main problem.

While Afghanistan is often blamed for the water shortage, its ambassador to Tehran, Nassir Ahmad-Nour, said it was wrong to view a country at war since 1979 as a culprit.

"The situation is even worse on our side of the border," he added.

© 2015 AFP