First sensor for 'crowd control' in cells

University of Groningen scientists have developed a molecular sensor to measure 'crowding' in cells, which reflects the concentration of macromolecules present. The sensor provides quantitative information on the concentration of macromolecules in bacteria and in mammalian cells. A description of the sensor and its validation was published in Nature Methods on 2 February.

Living cells are full of macromolecules like proteins and nucleic acids. This has a profound influence on the way molecules inside a cell interact. Crowding reduces diffusion, but it also means that molecules stay together more easily. For example, DNA transcription is a hundred times faster under realistic cellular conditions than under diluted laboratory conditions. Despite its importance, crowding is rarely taken into account in biochemical studies.

The main reason for this is the lack of a reliable measurement technique for crowding. So far, it was only possible to estimate crowding from the average concentration of macromolecules and average cellular volumes. The new sensor is able to measure crowding in living cells, with a resolution that allows for the visualization of intracellular differences in both time and space.

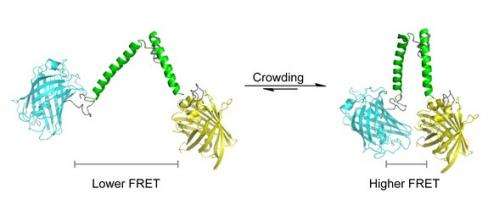

The new sensor was developed by Dr Arnold Boersma and Professor of Biochemistry Bert Poolman. They designed a protein 'spring' with fluorescent protein markers on both ends. The first marker emits a blue light when excited by laser light. This blue light in turn excites the second marker, which then emits yellow light. This transfer of resonance energy is proportional to the distance between both markers; the technique is called 'Förster resonance energy transfer' (FRET).

Macromolecules exert a mechanical pressure on the protein spring, forcing the markers closer together. A series of control experiments have ruled out that other forces (e.g. ionic strength or chemical affinity) affect the distance between both markers. Other experiments have shown that the sensor gives an accurate quantitative estimate of crowding in cells.

Artificial gene

The sensor is encoded on an artificial gene, which is expressed in the cells. Boersma and Poolman developed two versions of the gene: one for bacteria and one for mammalian cells. 'We will use this sensor to map the structure of the cytoplasm during the cell cycle', says Poolman. 'Our interest is in volume regulation, which obviously affects crowding. But it's easy to envision many other applications for the sensor.'

Information on crowding is important for Systems Biology and Synthetic Biology because the conditions inside cells influence interaction rates and affinities of biomolecules, folding rates and fold stabilities in vivo. 'We want to know how cells work, and how we can engineer designer cells', says Poolman, who is also scientific director of the Centre for Synthetic Biology at the University of Groningen. He expects the crowding sensor to contribute to a better understanding of cellular function.

The sensor was designed at the Groningen Biomolecular Sciences and Biotechnology Institute and the Zernike Institute for Advanced Materials,, University of Groningen, Groningen, the Netherlands.

More information: A sensor for quantification of macromolecular crowding in living cells, DOI: 10.1038/nmeth.3257

Journal information: Nature Methods

Provided by University of Groningen