Our invisible family tree could hold a key to the future

It's an ancient type of microorganism that makes up 20 per cent of the Earth's biomass, yet only now are scientists revealing the secrets of archaea.

In an international collaboration between research teams in Cambridge UK and Sydney, the function of a newly-discovered family of proteins associated with archaea has been uncovered, throwing light on an ancient protein superfamily that is vital for almost all life on earth.

The research, led by Dr Iain Duggin, Research Fellow at UTS's ithree institute, has been published recently in the journal Nature.

Archaea make up the third major grouping, or domain, of life on the planet, alongside eukaryotes (including all plants and animals) and bacteria, but are comparatively little studied.

They are believed to be amongst the oldest life forms on earth, having existed for some 2.5 billion years, and play a vital role in recycling the earth's elements.

They can survive in extreme conditions of cold, heat and salinity, exist in the soil, sewage, oceans, and oil wells, and even make up an estimated 10 per cent of the microbial population found within the human gut. They are also responsible for all biological methane, a major greenhouse gas, as occurs in cattle and other ruminants.

"Archaea and bacteria joined forces early in evolution, and all other complex life we see around us today is the result," Dr Duggin said.

Dr Duggin said a better understanding of archaea could have valuable applications across a wide spectrum of industries from oil exploration, to chemical processing, or as a new source of antibiotics.

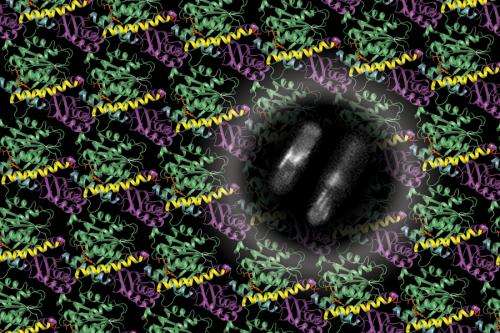

The family of proteins that were the focus of the research, called CetZ, act like a miniature skeletal system for archaeal cells, controlling their shape and movement. This "cytoskeleton" allows the cells to transform into a torpedo-like shape for faster swimming.

Scientists had thought this feature only evolved with more complex organisms, but the new findings suggest that such behaviour might have evolved earlier than previously thought and is an inheritance from archaea.

Where that comes into play for people – and bacteria – is that CetZ is related to a protein in humans that is the target of several major cancer treatments and in bacteria the related protein is crucial for cell division and multiplication.

"Our research helps understand the differences between the human (tubulin) and bacterial (FtsZ) proteins that are related to CetZ," Dr Duggin said.

"Whilst tubulin is a key target in cancer drug development, we believe that FtsZ could be an important target for the development of new antibiotics, potentially enabling the design of anti-infective drugs that inhibit bacterial cell division and growth, with fewer side-effects," he said.

Director of the ithree institute Professor Ian Charles said it was crucial to better understand the function of archaea in nature, as well as potentially exploit their properties for industrial and medical applications.

"A new type of potentially useful antibiotic called Archaeocin has recently been described that is derived from the archaea," Professor Charles said. "Archaea provide an untapped source of novel compounds at a time when alternatives are urgently needed given the rapid rise of resistance to existing antibiotics."

Dr Duggin collaborated with former colleagues from the MRC Laboratory of Molecular Biology in Cambridge UK, who conducted the protein crystallography. He joined the ithree institute in 2011 and became one of its early Fellows, where he carried out the molecular biology and microscopy at ithree's state-of-the-art Microbial Imaging Facility using time-lapse and OMX super-resolution imaging.

More information: "CetZ tubulin-like proteins control archaeal cell shape." Nature (2014) DOI: 10.1038/nature13983

Journal information: Nature

Provided by University of Technology, Sydney