Science to the rescue of art

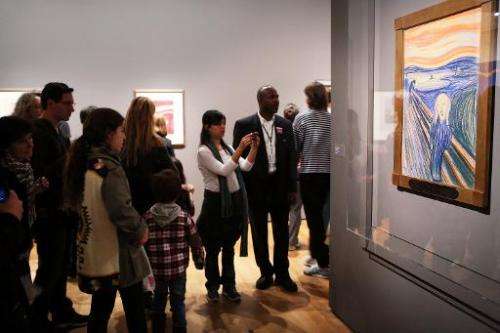

Vincent van Gogh's "Sunflowers" are losing their yellow cheer and the unsettling apricot horizon in Edvard Munch's "The Scream" is turning a dull ivory.

Some of our most treasured paintings are fading, warn experts who would like more money for the use of sophisticated technology to capture the masters' original palettes before the works are unrecognisably blighted.

"Our cultural heritage is suffering from a disease," Robert van Langh, director of conservation and restoration at Amsterdam's Rijksmuseum, told AFP in Paris this week.

"These priceless icons of our culture are deteriorating," he said. And the amount spent on conserving them "should be multiplied by ten."

Van Langh was speaking on the sidelines of a conference on the use of synchrotron radiation technology in art conservation at the molecular level.

Synchrotrons, stadium-sized machines that produce beams of bright X-ray light, are used to analyse the chemical degradation of famous artworks gracing the museums of the world.

Much more science is needed to understand the chemical reactions that cause colour changes in canvases, in order to stop them, said Jennifer Mass, an art conservationist from Winterthur Museum in Delaware, who also attended the meeting.

"There are heaps of researchers ready to do this work, but very little money."

Understanding the degenerative process would allow museums to display the precious works in the appropriate light, atmosphere and humidity.

But technology would also allow "digital reconstruction" of original pieces, as they were envisaged by their creators, for posterity.

"The goal is more preservation than restoration," said Mass, adding that restorers would only in very rare cases touch up the original work of an artist.

Fading like a flower

Experts already know that the iconic still life "Sunflowers" is browner today than when van Gogh captured it on canvas in 1888.

It turns out the Dutch Impressionist painter had opted for industrial pigments, then new on the market, for his yellows, according to Belgian chemist Koen Janssens of the University of Antwerp.

Exposed to air, the yellow in cadmium, also used by Munch for his 1910 work "The Scream", loses its brightness, while ultraviolet light—as from the Sun—turns it brown.

Janssens has also worked on van Gogh's famous "Flowers in a Blue Vase", which has suffered a similar fate but for a different reason.

In this case, it was a varnish applied after the artist's death that became cracked and faded over time, obscuring the picture underneath.

Synthetic pigments like cadmium yellow, emerald green and zinc yellow—some of which can start losing their depth of colour in only 20 years—were also popular among other Impressionists of the 19th century and painters of the early 20th like Henri Matisse and Pablo Picasso.

The works from this period are therefore more at risk of fading than those by the ancient masters, said Mass.

They are not exempt, though—for his blue hues the 17th century's Rembrandt van Rijn used smalt, a type of ground-up glass with a tendency to turn grey over time.

According to Janssens, a further role of science could be to beat the drum for art conservation.

"As researchers, we are working on a simulation that will allow us to show what certain artworks will look like in 50 years," if nothing is done, he said.

"If we don't act, future generations will not see these artworks in the same way that we are," warned van Langh.

© 2014 AFP