Researcher examines motion of breaking waves

During the spring of 2011, Lake Poinsett homeowners were amazed at how easily the waves destroyed their sandbag and concrete barricades, but South Dakota State University Civil Engineering Professor Francis Ting was not. He has been studying the motion of breaking waves for nearly 25 years.

"Waves a couple of feet high can produce tremendous forces" Ting said. As a result, he explained, "agencies are willing to put resources into protecting the coastline."

In recognition of his work with breaking waves, Ting was named Distinguished Researcher and Scholar for the College of Engineering at the Celebration of Faculty Excellence last month.

Ting began analyzing waves as a postdoctoral research fellow at the University of Delaware Center for Applied Coastal Research in 1989. After coming to SDSU in 1995, he has continued that collaboration through funding from the Office of Naval Research and the National Science Foundation. Since 2000, Ting has received more than $1 million to support his work.

"A flow pattern of a breaking wave has swirling motions like those in a tornado," Ting said. His research seeks to answer fundamental questions about the form and changing flow of these waves and how they interact with the bottom and transport sediment.

This information will help transportation engineers estimate the physical impact of water on bridges, dams and highways, he explained. "The idea is eventually to predict what might happen when, for instance, a storm or weather system hits a coastline."

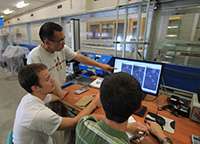

Ting and his team do the experimental work, while researchers at the Delaware research center perform the computer simulations. His current National Science Foundation project can support two graduate students and two undergraduate students.

To create the waves in the fluid mechanics laboratory, Ting uses a Plexiglas tank called a flume that is the length of two school buses and holds 4,500 gallons of water. The flume has a sloped bottom and a computer-controlled wave maker. As the mechanism moves, a laser illuminates tiny tracer particles in the water and a camera captures the motion of the waves.

Over the last two decades, Ting has gone from studying the movement of a single wave to a series of recurring waves and then to different types of waves.

"The basic equations of flow are well understood," Ting said, "but they can't be solved exactly." Because of this, approximations must be made. When these are implemented in a computer program, sometimes something neglected which might seem to be minor can have a significant effect on the modeling results, Ting explained.

Experimental work makes sure that those important processes are included in the simulation, Ting said. "If we don't do this, we could have a pretty picture with no relation to reality."

Predicting the behavior of breaking waves is difficult. "The surface of the water is constantly changing and folding in on itself," Ting said, "which makes understanding exactly what's going on challenging experimentally and computationally."

The challenge for Ting's team is to get good quality data, Ting explained. "Waves breaking incorporate air into the water, which then reflects light and obscures the motion of the tracers."

Once they are convinced that the data their experiments generate is real, Ting said, "we study the data to gain insight into the detailed flow structures." The team examines the wave's size, speed, rotation and other properties of fluid motion.

They must fully understand the action of the waves before they can begin considering issues such as erosion, Ting explained. "Sediment brings it to a new level of complexity."

His work thus far has been in two dimensions, but in May 2012 Ting purchased a laser and camera system to conduct 3-D imaging. While the two-dimensional system produced just one slide of the wave's motion, the new system captures a 3-D image of the flow pattern.

This spring or summer Ting and his team will tackle the analysis of breaking waves at a deeper level. They will use glass beads that have the same density and size as sand particles, he said "and see how the turbulence generated by breaking waves moves them about."

Once researchers can understand fundamentally how turbulence picks up bottom sediment in one specific setting, Ting said, "we can apply these basic physical mechanisms to other scenarios."

Only then will simulation and modeling be able to help scientists predict how waves will affect a coastline, Ting explained. This research will help community planners determine how to use resources effectively to protect the coastline or repair the damage.

Storms, such as Katrina and Superstorm Sandy, are catastrophic events, Ting said, "and unfortunately, they are becoming more common."

Provided by South Dakota State University