Battling oceanic climate change

Changes to the temperature and chemistry of Earth's atmosphere are causing fundamental changes to the ocean, too. The water is getting warmer and more acidic, and those changes may reconfigure the microbial communities that create the foundation of marine ecosystems.

USC Dornsife scientists are at the forefront of the efforts to predict the future for marine microbes, and to do that they are combining marine biology and evolutionary biology in the context of global climate change. This is a new field that requires new scientific models, said David Hutchins, professor of biological sciences in USC Dornsife.

"One emphasis is on developing new marine model organisms that are relevant to marine ecosystems and can be used in experimental evolution," he said.

These new models must address a kaleidoscope of conditions that determine the fate of marine microbes, said David Caron, professor of biological sciences and former interim director of the Wrigley Institute for Environmental Studies in USC Dornsife.

"It's not just the direct effects of changing ocean conditions on a particular species that are going to affect its success," he said. "It's those impacts plus the way all the other organisms in the community are responding that affect how a particular organism or a particular species succeeds or fails."

The microscopic impact of global climate change has been the subject of inquiry at USC for several years. Hutchins organized a conference in May 2010 at the Wrigley Marine Science Center that attracted 40 researchers from around the country to discuss themes for research on the evolutionary implications of ongoing physical and chemical changes to the ocean. Caron and Hutchins recently published an article in the Journal of Plankton Research to discuss new lines of research, and they are investigators for an ongoing grant from the National Science Foundation that led to the recent publication of a paper by a Ph.D. student in Hutchins' lab.

The USC Dornsife researchers are working in new territory with these experiments, considering the many combinations of changes that might occur in the ocean over coming decades, including changes to water temperature, water chemistry, oxygen levels and even clarity and penetration by ultraviolet light.

Hutchins said scientists already have subjected marine microbes to the warmer, more acidic conditions that are predicted for the future, but those experiments have typically run for only a few weeks. He said that is too short to determine if and how marine microbes might adapt.

"Most experiments have been very short term," he said. "You might take some phytoplankton and put them in acidic conditions for two or three few weeks and then try to understand the impacts on the organisms. A criticism of those types of experiments—and a valid one—is that stressors such as ocean acidification and global warming happen slowly, over a period of decades, and that organisms do evolve and adapt."

Changing environmental conditions might select for genetic variants that already exist and can thrive under the new conditions, or they may select for mutations within some species or strains that will give them a future advantage in water that is warmer, more acidic or both. Endless combinations of temperature and acidity might affect microbes in countless ways, and as each species reacts, it could start to prompt other reactions within its own microscopic community.

"You have to be cautious about interpreting short term experiments as fully predictive of long term trends," Hutchins said.

Caron, Hutchins and other USC researchers have been conducting the first of a series of long-term experiments on the reaction of microbes to increasing levels of carbon dioxide that's dissolved in seawater, a change that is lowering the pH of the water and making it more acidic.

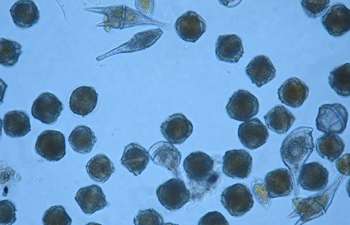

The experiment involved several species of dinoflagellates taken from local Southern California coastal waters, and it ran for one year.

Samples of microbes were incubated for two weeks at three different levels of dissolved carbon dioxide, all of them higher than normal. At the end of the incubation, samples of the dominant species were isolated and bred in separate cultures for up to a year, continuing at the higher CO2 levels. The microbes in these samples were no longer "naïve" about life under the higher levels; the survivors and their succeeding generations now had experience dealing with them and adapting to them.

The experiment was run by Avery Tatters, a Ph.D. student in Hutchins' lab within the USC Dornsife Marine Environmental Biology program.

"We focused on four dominant species of the dinoflagellates—the 'winners' of the initial experiment—that were alive at the end at the end of the two weeks," Tatters said. "We grew them separately under the higher CO2 concentrations in which they were isolated. Then, we periodically recombined them—at four, eight and 12 months—and assessed the competition."

The results of the research were published earlier this year in the online version of Evolution: International Journal of Organic Evolution.

Provided by University of Southern California