Unearthing the mechanisms controlling plant size

Plants have been cultivated and studied from the earliest days of human civilization, yet much remains unknown about them. A good example is the mechanism by which the size of plant cells is determined. Keiko Sugimoto, leader of the Cell Function Research Unit in RIKEN's Plant Science Center, in working to elucidate this mechanism has discovered a series of genes that control cell division or cell growth, attracting the attention of researchers and companies worldwide. "Our research focuses on the cellular aspects of plants," says Sugimoto.

A garden of lilies

While a high-school student, Sugimoto noticed that a single lily that had blossomed in her garden the year before had become three lilies a year later, followed by ten the next year and as many as 100 the year after. “But what impressed me most was that all of those flowers were the same size, and had the same color and same shape every year,” she says. “Although I knew that this was a manifestation of heredity, which I had learned at school, I was fascinated. I wanted to understand the mystery of plants, and this led me into research.”

After completing her master’s course in Japan, Sugimoto gained her PhD in plant science at the Australian National University. She then went to work at the John Innes Center in the UK—a Mecca for researchers studying plant biology—and in 2007 she set up the Cell Function Research Unit in RIKEN’s Plant Science Center. “How is plant cell size controlled? We are now working to solve this difficult problem.”

The aspect that had impressed Sugimoto most as a high-school student was that the sizes of flowers, leaves, seeds and other plant organs depend roughly on the species of plant. Each organ grows as its cells self-divide and increase in number, and each cell expands. However, plant organs do not continue to grow infinitely. “Flowers and leaves stop growing when they reach a certain size. Research has shown that plant hormones such as auxin and cytokinin are involved in plant growth, but we still don’t know how plant hormones control cell division and cell expansion to determine ultimate organ size,” says Sugimoto. “Plant size cannot be understood without knowing what is happening in cells. We are conducting research focusing on the cellular aspects of plants, which is a unique approach.”

Determinants of plant growth

“Every time I cut radishes or carrots into long, thin strips for cooking, I cannot help admiring the slices for a moment,” says Sugimoto with a smile. “If you look closely at a slice, you can see a finely textured portion near the tip. This is called the meristem. It is dividing tissue where the cells self-divide. Try taking a look next time you’re preparing a meal.”

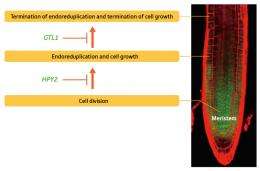

In plants, meristems are found only in the tips of roots and stems. Plant growth is the result of cell division and proliferation at the meristem, which is followed by cell expansion. “There are two key time points in plant growth. One is a turning point when cell division switches to cell expansion. Once a cell begins expanding, it cannot return to the stage of proliferation by division. The other is the point when cell growth stops and cells no longer expand. Plants cannot grow normally unless these two points are strictly controlled.” Sugimoto and her colleagues have attracted global attention for their discovery of the genes that control these two growth points.

Genes control cell division and endoreduplication

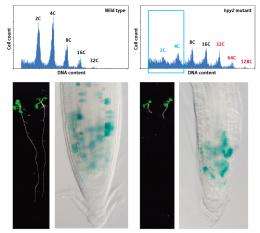

Sugimoto used a new technique to discover genes that control the point at which cells stop dividing and begin increasing in size. “Many researchers have tried to look for genes that control cell size, but most of them were trying to find mutants with altered cell size. Mutants have been identified merely based on the appearance of cells. We developed a method to accurately measure nuclear DNA content and isolate mutants with altered DNA levels.”

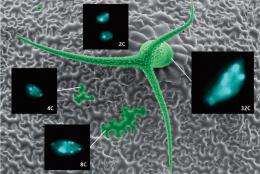

The cells of Arabidopsis, a commonly used experimental material in plant science, just like human cells, have two sets of chromosomes, one from the mother and the other from the father. The DNA of a cell having two sets of chromosomes is denoted 2C. When a 2C cell divides, its DNA is first replicated to produce 4C, which is then equally distributed into the next two dividing cells, resulting in two 2C daughter cells. In Arabidopsis, however, 2C and 4C cells are not the only cell types to be found. Gametes (pollen, ovules) that have undergone meiosis, a special process of cell division that results in half the number of chromosomes as found in somatic cells, are 1C cells, but there are also 8C, 16C and 32C cells. “In plant cells, DNA replication is sometimes followed by doubling in DNA without mitosis,” says Sugimoto. “This phenomenon is called endoreduplication, which results in 8C, 16C and 32C cells. The nuclear DNA and cell size are correlated; cells expand as their nuclear DNA increases.”

Together with Takashi Ishida, a postdoc in her lab, Sugimoto examined the nuclear DNA content of Arabidopsis cells and discovered a mutant having fewer 2C and 4C cells and more 32C, 64C and 128C cells. “Usually in plants, 2C and 4C cells in meristems continue to divide at a constant rate. We assume that in the mutant we discovered, these meristematic cells have undergone endoreduplication and switched into cell expansion prematurely. A more detailed investigation revealed that this mutant had lost the function of the HPY2 gene. Hence, HPY2 plays a role in controlling the point of switching to endoreduplication, where cells stop dividing and instead grow in size.”

This achievement was announced in August 2009, drawing attention not only from plant biologists, but also from researchers studying a wide variety of other organisms. “This is because HPY2 is involved in the function of a small peptide known as SUMO, a small ubiquitin-like modifier. SUMO is found in a broad range of species, from humans to plants and yeasts. It binds to other proteins to enhance or weaken their functions, and to regulate the diverse functions of cells. The reason why my result attracted so much attention is that researchers studying diverse ranges of organisms have been interested in SUMO.”

Sugimoto’s group demonstrated that the protein produced by HPY2 mediates the binding of SUMO to other proteins, resulting in the regulation of cell division. This was the first report of SUMO being associated with the regulation of cell division in multicellular organisms. “I never thought that my studies on the mechanism of plant cell size control would lead to SUMO. Research is fascinating because it can lead to unexpected results.”

Sugimoto has also discovered three other genes that control the switch into endoreduplication like HPY2. Her next task is to clarify the differences in their functions.

A gene terminating cell growth

In September 2009, following the discovery of HPY2, Sugimoto’s group discovered a gene involved in the second point—when plant cells stop growing in size. “It began with the discovery of a mutant having very large trichomes by Christian Breuer, a posdoc in my lab, who was searching for mutants with abnormal cell size.”

Trichomes are hair-like outgrowths that cover the surfaces of Arabidopsis leaves to protect them from insects, pathogens and even ultraviolet radiation. “Each trichome comprises a single epidermal cell in Arabidopsis. It is large enough to be seen macroscopically.” While even a normal-sized trichome is 500 times larger than an ordinary cell, the mutant discovered by Breuer has trichomes that are more than twice this size.

The mutant was found to have the GTL1 gene partially modified and expressed in excess. When the function of GTL1 was artificially suppressed, the mutant’s trichomes became more than twice the size of wild-type trichomes. Based on these experiments, Sugimoto’s group hypothesized that GTL1 functions to terminate cell growth. To test the hypothesis, they examined when and where GTL1 is expressed. It was found not to be expressed in smaller trichomes in the early stage of growth or trichomes that had stopped growing, but to be expressed only in trichomes that have just expanded to maximum size.

Previously, it had been thought that cell growth ceases when the supply of cellulose and other components of the cell wall is stopped, or when water absorption in vacuoles ceases. However, the discovery of GTL1 shows that plants have an intrinsic mechanism for actively stopping cell growth. The discovery is groundbreaking, overturning the traditional concept of plant growth.

Trichomes are cells undergoing endoreduplication, which is known to cease at 32C. Sugimoto’s group is conducting research on the hypothesis that GTL1 may control endoreduplication. It is already known that the function of the gene necessary for endoreduplication is activated in mutants lacking the function of GTL1. “GTL1 produces a protein known as a transcription factor, which binds to the DNA of a certain gene to promote or suppress its transcription to RNA. In the future, I want to clarify how GTL1 controls transcription and of which genes, and to discover the mechanism of endoreduplication.”

Giant prospects

Since the announcement of the discovery of GTL1, Sugimoto has received a flood of offers for joint research, including many inquiries from industry, who have great expectations for creating larger fruits and vegetables by suppressing the function of GTL1.

Some cultivars are already available with increased yields thanks to artificial duplication of nuclear DNA with chemical agents. However, this chemical treatment unavoidably duplicates the nuclear DNA in all cells constituting the plant body, which in turn makes the plant unable to produce seeds. “Advanced research on GTL1 may allow us to promote endoreduplication at desirable portions of plants, such as fruits, flowers and leaves, or whenever needed, to change their sizes without preventing seed production,” says Sugimoto, who is keen to conduct joint research with industry.

“Now is the most enjoyable time in my academic career,” declares Sugimoto. However, she is not satisfied with just discovering the genes that control plant growth. Further extensive investigation of the functions of individual genes is needed. It is also necessary to identify the targets of HPY2 and GTL1 to determine on which genes and proteins they act. She is also interested in the relationship between HPY2 and GTL1, and their association with plant hormones. “Much remains to be done, and I have not found the answer to my question about lilies when I was a high school student. In the plant kingdom, there are so many unanswered questions. This is why I am fascinated by plant research.”

Provided by RIKEN