Researchers uncover new cell biological mechanism that regulates protein stability in cells

The cell signaling pathway known as Wnt, commonly activated in cancers, causes internal membranes within a healthy cell to imprison an enzyme that is vital in degrading proteins, preventing the enzyme from doing its job and affecting the stability of many proteins within the cell, researchers at UCLA's Jonsson Comprehensive Cancer Center have found.

The finding is important because sequestering the enzyme, Glycogen Synthase Kinase 3 (GSK3), results in the stabilization of proteins in the cell, at least one of which is known to be a key player in cancer, said Dr. Edward De Robertis, senior author of the study and a Jonsson Cancer Center scientist.

"Surprisingly, we found that the degradation of about 20 percent of proteins in the cell is triggered by the GSK3 enzyme," said De Robertis, who also is a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator. "That's a great many proteins and one of them, beta-Catenin, is known to cause cancer. We also know that Wnt signaling is activated in about 85 percent of colorectal cancers and other forms of cancer start with mutations that activate Wnt signaling. So, this finding could have ramifications for potential new treatments for cancer."

The study, a collaboration with cell biologist Dr. David D. Sabatini of New York University, appears in the Dec. 23, 2010 issue of the peer-reviewed journal Cell.

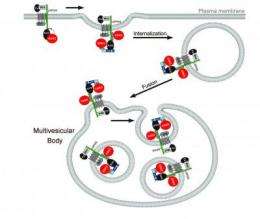

De Robertis said Wnt signaling requires inhibition of GSK3, but the enzyme sequestration mechanism was not known until now. The enzyme becomes imprisoned inside membrane-bounded organelles, known as multivesicular bodies, found within the cell cytoplasm.

"We knew these multivesicular bodies were involved in degradation of proteins, but that they had a role in how cells communicate with each other by switching on a signaling pathway was not known," De Robertis said. "This finding raises the possibility that other signaling pathways could operate through this sequestration mechanism."

When cells receive Wnt, it's a signal for cells to degrade their proteins more slowly, to keep them for a longer period of time because they're needed to regulate cell functions, such as proliferation. Wnt signaling, for example, is very high in all stem cells and rises during the regeneration of most tissues, De Robertis said.

"Perhaps one of the functions of Wnt is to stabilize certain cell functions and it may be that cancer needs higher protein stability than other cells, which is why increased Wnt signaling if found in so many cancers," De Robertis said. "These findings may give us new therapeutic targets for preventing sequestrations inside these membranes, which would decrease Wnt signaling."

De Robertis said this study also links two formerly unrelated areas of biology. The cell cytoplasm is filled with internal membranes that shuttle proteins to their final destinations. Cells in tissues communicate with their neighbors by receiving external signals called growth factors. The new work links the cell biology of membrane trafficking and the interpretation of the signals that control cell proliferation.

"Protein degradation is a very important part of the life of a cell. About 10 percent of the genes in the genome are dedicated to protein degradation," De Robertis said. "We now know that Wnt causes an enzyme that degrades proteins to be sequestered and because of that becomes a regulator of cellular protein stability."

De Robertis characterized this finding as "very unexpected."

"No one thought you could have cell signaling through sequestration of an enzyme inside a membrane organelle like these multivesicular bodies," he said. This is because the GSK3 enzyme is normally found everywhere in the cell, but becomes tightly bound to the internal side of membrane receptors when the Wnt signal is received.

Provided by University of California - Los Angeles