Time (and PPAR-beta/delta) heals all wounds

Mammalian skin requires constant maintenance, but how do skin cells know when to proliferate and at what rate? In the March 23, 2009 issue of the Journal of Cell Biology, Nguan Soon Tan and colleagues reveal that skin fibroblasts use a protein called PPARβ/δ to make sure overlying epithelial cells don't proliferate too quickly. Their results highlight how communications between different cell types are critical to maintain the skin as a barrier against the outside world.

Skin has two main layers: the underlying dermis, made up of fibroblasts and other cells, and the outer epidermis, containing epithelial keratinocytes. Signals are exchanged between these layers to coordinate their function, but dissecting these signals is tricky. For example, PPARβ/δ is an important protein for maintaining healthy skin, but its precise function remains controversial.

PPARβ/δ is a nuclear hormone receptor that regulates gene expression. In mice lacking PPARβ/δ, epidermal cells proliferate excessively after wounding (1). But cultured keratinocytes from these mice don't proliferate any faster than normal cells and, in fact, are more susceptible to apoptosis (2). According to Nguan Soon Tan, this discrepancy was the first indication that PPARβ/δ might regulate crosstalk between layers of the skin—the epidermal hyperproliferation seen in the knockout mice could be due to faulty signals from the dermal cells.

But this couldn't be studied further in mice, as it is not yet possible to delete a gene exclusively from the dermis. "We had to look at a situation where the different types of cells were not in isolation but could communicate with each other," says Tan. "Organotypic skin cultures are a really good technique for this."

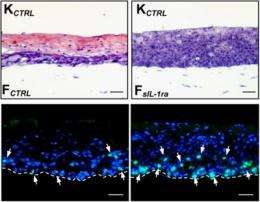

First developed in the 1980s (3), organotypic skin cultures (OTCs) are made by embedding dermal fibroblasts in a gel of extracellular matrix proteins. Keratinocytes are seeded on top of this gel and the two cell types develop into an in vitro version of skin that looks remarkably like the real thing. The fibroblasts and keratinocytes can therefore be manipulated separately—knocking down or overexpressing proteins— before the skin is reconstructed.

Chong et al. found that PPARβ/δ-deficient fibroblasts made wild type keratinocytes hyperproliferative in OTCs by secreting extra doses of several growth factors. The fibroblasts were stimulated to produce these growth factors by keratinocyte-released cytokine IL-1 - underscoring the reciprocity between the two cell types. Blocking either the IL-1 signal or any of the growth factors released by the fibroblasts returned the OTCs to normal.

So why do fibroblasts lacking PPARβ/δ send out more growth factors in response to IL-1? The authors discovered that PPARβ/δ stimulates the production of sIL-1ra, a protein that inhibits IL-1 signaling by competing for the IL-1 receptor. Normally, this would decrease the IL-1 signal received by fibroblasts and therefore reduce the growth factor signals sent back to the keratinocytes. But in PPARβ/δ's absence, fibroblasts keep stimulating keratinocyte division. Similarly, PPARβ/δ knockout mice expressed less sIL-1ra after wounding and produced more growth factors that stimulate the epidermis. "Proliferation is important in early stages of wound healing," explains Tan. "But excessive proliferation isn't good: you can end up with hypertrophic scarring."

This may also be critical to prevent tumor development. Contradictory reports exist on whether PPARβ/δ promotes or inhibits epithelial cancers (4-6). Tan's group has already found that fibroblasts lacking the protein can increase the proliferation of squamous carcinoma cells; they now plan to investigate PPARβ/δ's expression in tumor-associated fibroblasts. "Fibroblasts often play important roles by communicating with epithelial cells," says Tan. "But dissecting these networks has been very difficult. We've managed to show how one particular nuclear factor in fibroblasts can have a wide ranging effect on a tissue."

More information:

1. Michalik, L. et al. J Cell Biol 2001 154: 799-814.

2. Tan, N.S. et al. Genes Dev 2001 15: 3263-77.

3. Bell, E. et al. Science 1981 211: 1052-54.

4. Barak, Y. et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2002 99: 303-8.

5. Gupta, R.A. et al. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 2000 97: 13275-80.

6. Harman, F.S. et al. Nat Med 2004 10: 481-83.

Chong, H.C., et al. 2009. J. Cell Biol. doi:10.1083/jcb. 200809028.

Source: Rockefeller University (news : web)